|

After the rehang

Plain Bob Major Simulated Ringing |

The original bells

Bristol Surprise Major Simulated Ringing |

|

|---|

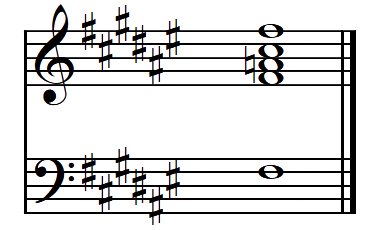

The true-harmonic tuning of a bell aims to bring its five lowest partial tones to a simple musical relationship. These particular tones in the St Giles eight are shown in the table below. Large characters represent the retuned bells, with their pre-tuned values shown in small beneath. They were calculated using Wavanal to analyse audio recordings of the individual bells ringing full-circle. The hum is the lowest tone (a sub-harmonic), with the prime being one octave above it (twice its frequency). The tierce is then a minor third (three semitones) above the prime; the quint is a perfect fifth (seven semitones) above the prime. The next octave above is the nominal (four times the frequency of the hum).

Hum F0♯ · Prime F1♯ · Tierce A1

Quint C2♯ · Nominal F2♯

Using an equally tempered scale, the theoretical values for the nominal frequencies are shown in the left-hand column of the table (Wavanal also assumes equal temperament in its calculation of the note values). Note that an equally tempered scale is exact only for the note A1 = 440Hz and all of the octaves of A above and below it. The frequencies of the other notes are approximations, with a given semi-tone being related to the one below it by a factor of one twelfth root of two. This gives an integer ratio only for twelve semi-tones or one octave. On the other hand, just intonation relates notes by ratios of small whole numbers and this sounds precisely consonant in a given key. Because I do not know the temperament that was used by Whitechapel in their tuning, I cannot therefore give an exact value for the expected nominals. However, it is clear from the table that these five partials now conform more closely to equal temperament.

| Bell Equally tempered nominal | Hum | Prime | Tierce | Quint | Nominal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Note | Hz | Note | Hz | Note | Hz | Note | Hz | Note | Hz | |

| F♯3 1480.0Hz Treble | G1-24 G♯1+11 | 386.5 418 | F♯2-31 F♯2+14 | 726.5 746 | A2+22 A♯2+18 | 891.5 942.5 | D3-25 D#3+06 | 1157.5 1249.5 | F♯3-31 G3-31 | 1453.5 1539.5 |

| E♯3 1396.9Hz Second | F♯1-35 G1+26 | 362.5 398 | E2+01 E2+17 | 660 666 | G♯2-04 A2-42 | 828.5 858.5 | C3+03 D3+15 | 1048.5 1185.5 | F3-42 F3+27 | 1363 1419.5 |

| D♯3 1244.5Hz Third | E1-32 F1-28 | 323.5 343.5 | C♯2+20 C♯2+08 | 561 557 | F♯2+15 G2-42 | 746.5 765 | A♯2-19 C3-41 | 922 1021.5 | D♯3-16 E3-49 | 1232.5 1281.5 |

| C♯3 1108.7Hz Fourth | D1-45 D♯1-06 | 286 310 | C♯2-45 C♯2-37 | 540 542.5 | E2+03 F2-07 | 660.5 695.5 | G♯2+27 G♯2-11 | 844 825 | C♯3-40 D3-31 | 1083 1153.5 |

| B2 987.8Hz Fifth | C1-37 D1-30 | 256 288.5 | A♯1+03 A♯1+37 | 467 476.5 | D2+00 D♯2+07 | 587.5 625 | G♯2-13 G♯2+29 | 824 845 | B2-33 C3-23 | 969 1032.5 |

| A♯2 932.3Hz Sixth | B0-49 C1-34 | 240 256.5 | A♯1-47 A♯1-17 | 453.5 461.5 | C♯2-12 D2-35 | 550.5 575.5 | F♯2-48 G2-33 | 719.5 769 | A♯2-46 A♯2+23 | 907.5 945 |

| G♯2 830.6Hz Seventh | G♯0+39 A0-03 | 212.5 219.5 | G1+39 G1+08 | 401 394 | B1-13 B1+17 | 490 499 | D♯2-40 E2-16 | 608 653 | G♯2-36 G♯2+15 | 813.5 838 |

| F♯2 740.0Hz Tenor | F♯0-37 F♯0+32 | 181 188.5 | F♯1-37 F♯1+09 | 362 372 | A1-11 A♯1-45 | 437 454 | C2+35 C♯2-26 | 534 546 | F♯2-36 F♯2+26 | 724.5 751.5 |

Almost all of the re-tuned notes in the table above are now lower in frequency. This lowering is the result of the tuning technique, in which an annulus of metal is removed from around the inside of the bell using a lathe. This makes the inner profile larger and so its partials therefore fall in value (just as a longer string will vibrate with a lower tone). However, removing metal from one place inside the bell affects more than one partial and so the bell-founder's skill is needed to bring the partials into tune with each other. Of course, removal of metal from the outside would obliterate any inscriptions or other features, and so the outer profile must therefore generally remain fixed as it was cast. Note that the frequency of a bell's note varies with the square of its thickness, and inversely with its diameter.

Clicking on a bell number in the table below allows you to compare each of their sounds. There's quite a noticeable reduction in frequency if you compare each. Now, examine the relationship between the treble and the tenor in both cases (they should each be one octave apart). To me it seems odd that the old tuning appears to give a more satisfactory octave than the new one, even though the lower five partials of the retuned bells are more correct. So why is this?

|

After the rehang |  |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| The original bells |

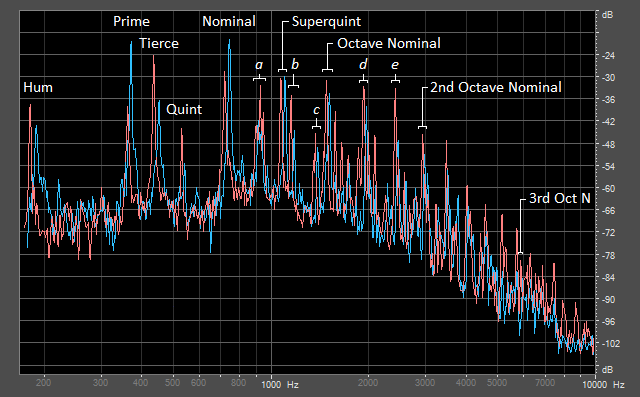

The graph below shows the frequency spectrum of the tenor, before and after tuning. The left-right axis represents frequency on a logarithmic scale, meaning that the distance between successive octaves is equal (even though an octave actually represents a doubling in frequency). The height of each peak shows its relative sound pressure level in decibels (dB). An increase of 6dB represents a doubling in sound pressure level, while a doubling in perceived loudness corresponds to about 10dB at 1000Hz. The two spectra were captured at a point in time where the hum notes had peaked in volume. By clicking on any of the names of the partials in the graph, you can hear just that partial on its own (as extracted from the tuned tenor). Note that the 3rd octave nominal is so quiet that you might not be able to hear it.

Orange: after tuning Blue: before tuning

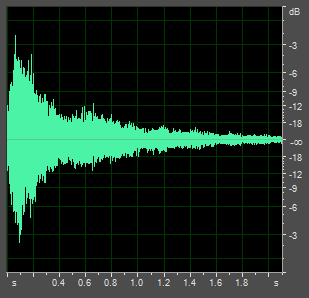

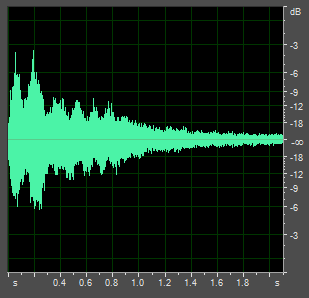

It is clear from the spectra above that many frequencies of sound are present. These are due to the different modes of vibration in the structure of the bell. The way in which the ear assigns a unique strike note to this complex sound is not well understood. Bill Hibbert explains it as the phenomenon of virtual pitch. The virtual pitch, or strike note, is a tone which corresponds roughly to the frequency of the prime. That is, even if a prime tone were not present, a prime strike note will still be perceived. In other words, it is manufactured, either by the ear or by the brain. You can test this theory yourself by using the tables below, where the original bell sounds have had their prime tone removed. This extracted prime also appears in the same table. Additionally, by listening to the prime of the old tenor, it becomes clear that the clapper is striking twice; this can be seen visually in the right-hand graph below the tables.

|

The restored treble Minus its prime The extracted prime F#2-31 726.5Hz The note I whistled F#2-20 731Hz |

The original treble Minus its prime The extracted prime F#2+14 746Hz The note I whistled G#2-23 773.5Hz |

|

The restored tenor Minus its prime The extracted prime F#1-37 362Hz The note I whistled F#1-28 364Hz |

The original tenor Minus its prime The extracted prime F#1+09 372Hz The note I whistled F#1-02 369.5Hz |

Sound pressure (dB) against time (s)

Sound pressure (dB) against time (s)

The easiest way I found of determining a strike note was to whistle while listening to an audio recording of the bell. By recording my whistled note, I could then use Wavanal to determine its frequency. What I actually whistled was twice the frequency of the prime, so I halved this and placed an audio representation in the table above. The new bells are now perfectly in tune while, even though the prime of the old treble is close to the expected value, the note I whistled is almost two semi-tones sharp of this. In conclusion therefore, I am not able to explain why the new treble does not seem to sound an exact octave above the tenor. Do please email Andy Dunn if you can enlighten me.